Nor-Cal Guides and Sportsmen’s Association: The Sportsman’s Voice

Subscribe to The Fish Sniffer

Stay up to date with the latest fishing reports and expert tips.

Stay up to date with the latest fishing reports and expert tips.

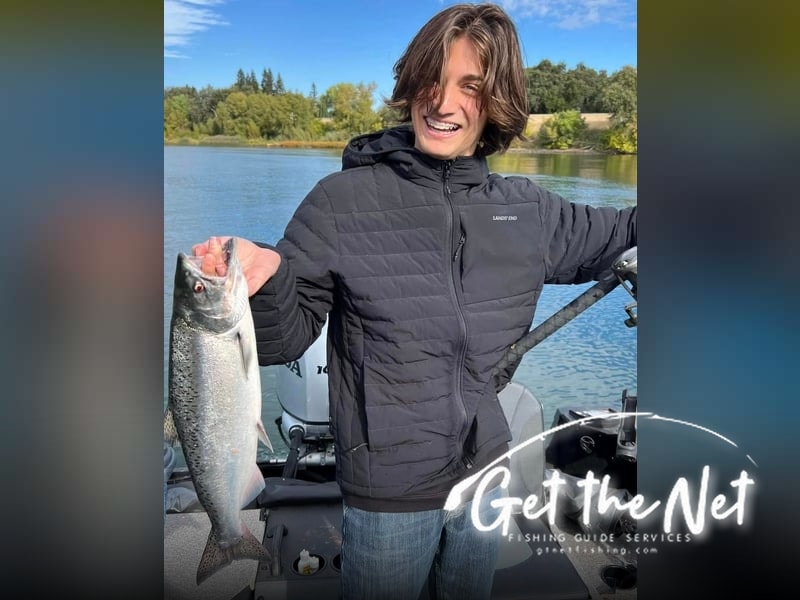

It isn’t final yet but it looks like we’ll have some sort of salmon season this fall on the Sacramento River. If that is the case, I will be booking trips for individuals and small groups of no more than 3 adults or 4 people if kids are part of the mix. It will be personalized fishing and a chance to not just catch, but learn. I’ll update when I know more. Keep your fingers crossed!

One more week (Feb 23rd) until we get the Reel Addiction 2 boat in the water Sturgeon Fishing out of Pittsburg. You go ahead and book online now with Captain Shawn Taylor. 🚨 The first week he will be running some DISCOUNTED scouting trips.. 👀 ‼️ Call Captain Shawn 510-815-4886 for more information on those. Can pay cash and he will put you on the calendar now! Book Online for dates after the first week

Spring is just around the corner! To say I’m excited to be back on the river with everybody again ain’t even beginning to tell the story! These are some of the BEST days! If you don’t already know, you gotta book early if you want a spot 😄 Call me, message me here or Here Fishy Fishy! I can’t wait to see you out there catching some sun… and some fish!

Nor-Cal Guides and Sportsmen’s Association: The Sportsman’s Voice The Nor-Cal Guides and Sportsmen’s Association (NCGASA) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit that speaks for over 2,500 professional guides and e...

Meet the Pro: Jeff Lechtaler of Lechtaler Guide Services If you have been watching the reports lately, you know the bite...

Tom Guzman knows that when Irvine Regional Park drops 800 pounds of fresh trout into the water, you’ve got to show up wi...

The Toyota Tacoma is essentially the unofficial uniform of the fishing world. Whether it is parked at a crowded boat ram...

Lawrence Ngai from Durasnare went poke-poling at low tide and brought back a good haul: one greenling, one monkeyface prickleback eel, three rock crabs, and 10 pounds of mussels. Nice mix from the Cal...

Reel Addiction Sportfishing out of San Francisco Bay is doing lots of prep and has exciting things coming up for the upc...

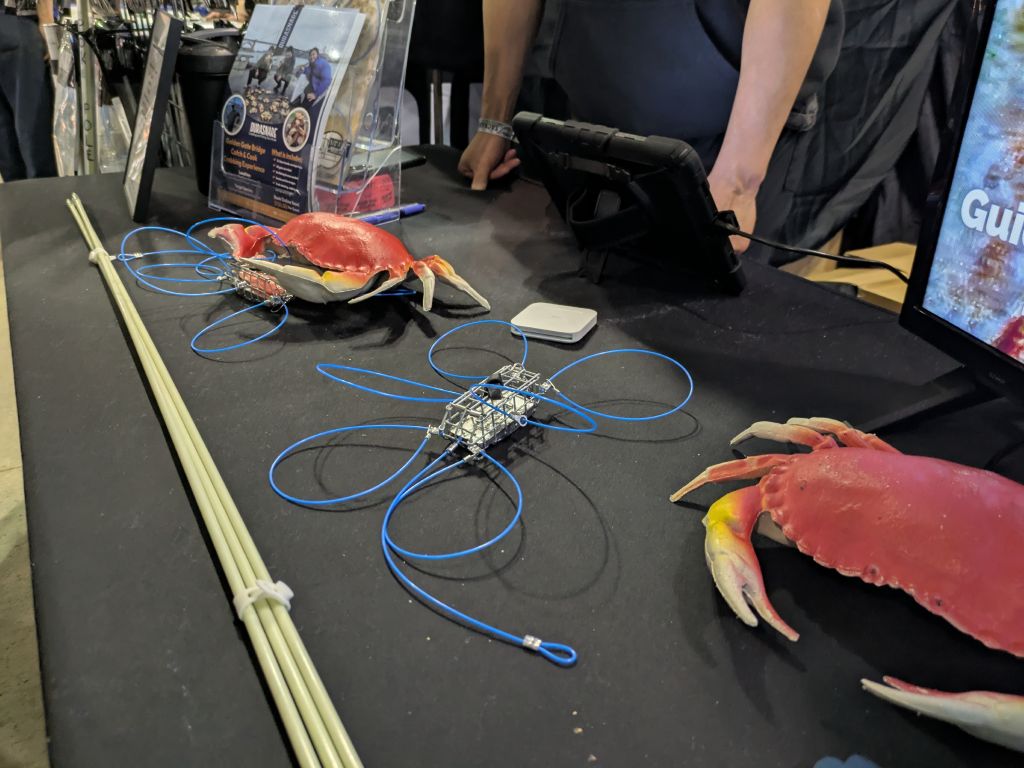

The Fish Sniffer team had a great time at the International Sportsmen's Expo this weekend. It was awesome to catch up wi...

The Fish Sniffer team had a great time at the International Sportsmen's Expo this weekend. We enjoyed meeting up with ou...

Check out the new Issue of The Fish Sniffer magazine for February 13, 2026.

In this issue of The Fish Sniffer, we are moving from Winter into early spring. The wonderful, mild weather we have had all through January and February has caused most of the rivers, lakes and reservoirs to be in very good shape. Most are nice and clear, and the water temperatures are warmer than usual, causing fish of all sort to get more active and bite better!

In this issue of The Fish Sniffer, you will read about outstanding trout fishing in many reservoirs, including Folsom, New Melones, and others, including a monster 17 pound rainbow trout caught at Lake Natoma. Black bass fishing has also been very good at many lakes, and Clear Lake has been kicking out some monster bass. And be sure to read Craig Nelson’s article about fantastic crappie fishing at Clear Lake as well. Pyramid Lake north of Reno continues to kick out tremendous Lahontan cutthroat trout to 20 pounds. Check out Dan Bachers conservation features and you are invited to a public Salmon Information meeting of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife concerning salmon fishing in Northern California.

The golden mussel problem is still impacting boaters all over the state and has caused major boat launch closures and strict new inspection and quarantine rules several lakes in our area. These rules are starting to change, with Lake Pardee and Lake Comanche announcing they will allow outside boats on their waters next year, with banding and inspections in place. Be sure to check out the regulations at any lake you want to fish before you go. All you need to know about fresh and saltwater fishing in Northern California is now available in the new issue of The Fish Sniffer Magazine!

Nor-Cal Guides and Sportsmen’s Association: The Sportsman’s Voice The Nor-Cal Guides and Sportsmen’s Association (NCGASA) is a 501(c)(3) non-profit that speaks for over 2,500 professional guides and e...

Meet the Pro: Jeff Lechtaler of Lechtaler Guide Services If you have been watching the reports lately, you know the bite...

The Toyota Tacoma is essentially the unofficial uniform of the fishing world. Whether it is parked at a crowded boat ram...

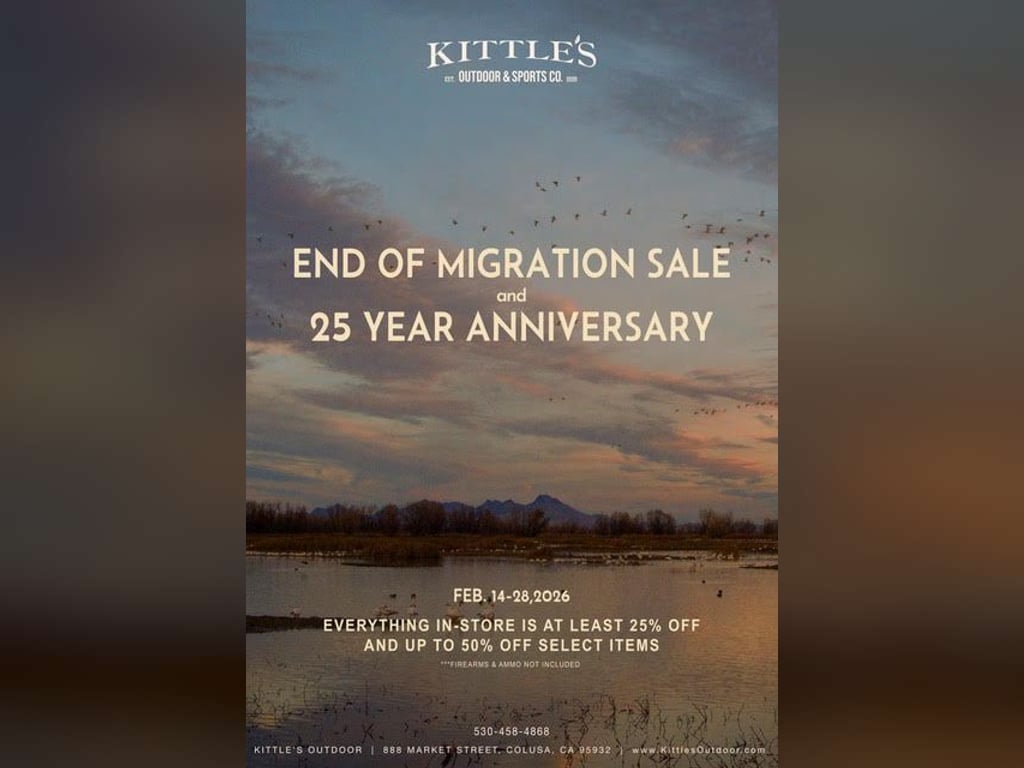

Kittle’s Outdoor Sports in Colusa is celebrating 25 years in business and offering a fantastic sale on EVERYTHING in the...

Mike Cooper of MADE Baits caught this brown in the Eastern Sierras. He hit the river reservoir edge during the tail end of a fall storm before check in and found a heavy pumpkin colored buck brown. It...

BURSON – Shore anglers and rental boaters are catching big numbers of black bass, particularly smallmouths, at Pardee La...

ANGELS CAMP – While kokanee salmon fishing has petered out as the fish go upriver to spawn, fishing for rainbow trout is...

SANTA CRUZ – While most anglers are focusing on rockfish and lingcod now that all depths are open, a few bluefin tuna ar...

Jack Naves made three trips to Collins Lake, landing trout up to seven pounds. He ran his North River Boat powered by Yamaha, guided by a Minn Kota trolling motor. He employed Edge Mag Pro Rods in Cannon downriggers and ClearBoard side planers. The rods were teamed with Abu Garcia Max Toro DLC line-counter reels spooled with Trilene XT 14-pound test clear mono. They trolled Arctic Fox trolling flies with Wiggle Fin Action Discs tipped with red worms, plus Rapala F09 Floating Minnows in the ‘Hot Steel’ color. 4-foot leaders were made of 12-pound test Seaguar InvizX fluorocarbon line.

Paul Kneeland fished Rollins Lake from the shore. He caught rainbow trout to 13 inches casting small silver Kastmaster and Jake’s spoons using a 7 foot Wade Rods ultralight spinning rod with a Abu Garcia Revo STX reel loaded with 15 lb test Stren sinking braided line in water 10 to 30 feet deep off the dam.

Dan Bacher fished for rainbow trout from shore at Sugar Pine Reservoir. He used a Berkley Ugly Stik GX2 6’ 6” medium action spinning rod, teamed up with a Shakespeare GX235 spinning reel filled with 8 lb. test P-Line CX Premium Fluorocarbon Coated Line. He used Berkley Tequila Sunrise Power Bait on a #14 Eagle Claw gold treble hook on a sliding sinker rig.

Hefty largemouth bass are the reward for anglers using live scopes to locate fish. Use shad pattern swimbaits, jigs and other lures for the best success.

Holdover rainbows, recent planters and king salmon are being caught by experienced anglers. Troll with Trout Trix Worms, Speedy Shiners and other lures from the surface to 25 feet deep.

Sanddabs, along with petrale sole and mackerel, are the reward for anglers venturing out on charter boats out of Santa Cruz and Monterey. Tom’s jigs, tipped with squid strips, are the top lures.

Trollers are catching rainbow trout on spoons and plastic worms behind dodgers. Shore anglers are hooking trout while tossing out PowerBait and nightcrawlers.

The spotted bass action should shift into high gear for anglers using small swimbaits and soft plastics. Expect to catch fish in the 15 to 25 foot range.

Fishing for striped bass is tough on the Delta. However, anglers trolling Dredger lures and spooning in the Port of Sacramento and Deep Water Channel are catching fish averaging 6 pounds.

The stretch of river below Nimbus Fish Hatchery is producing steelhead. Anglers are throwing spoons, drifting nightcrawlers under floats and pulling an array of plugs.

The steelhead season is in full swing. Boaters are hooking bright steelies while pulling plugs, while shore anglers are using fish pills, yarn and salmon roe.

Rainbow and brown trout are hitting flies on the Truckee River. The stonefly hatch is expected to begin in March.

Steelhead fishing has been tough since dam removal. However, one guide reported catching and releasing 6 adult fish while fly fishing on a recent trip.

The lake reopened to fishing on February 6. 4,000 pounds of rainbow trout went into the reservoir before the opener

Catch-and-release sturgeon fishing has been productive. Use ghost shrimp, salmon roe and lamprey eel for the sturgeon.

Rockfish and lingcod season will begin on April 1. Expect to bag limits of colorful rockfish, along with lingcod, while using bars, jigs and shrimp flies.

It won’t be long before the striper run begins in the Sacramento and Feather rivers. The fish typically start moving into the rivers in early March.

Expect the perch fishing to pick up off the Sonoma County Coast in March and April. Toss out pileworms, shrimp and plastic grubs for the best action.

Bay Area party boats will begin trolling anchovies and herring for halibut in March. This should be another great halibut season.

CDFW to Host Public Meeting on California’s Salmon Fisheries Sacramento - The California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) invites the public to attend its annual Salmon Information Meeting. The ...

SACRAMENTO — Opponents of the Delta Tunnel project last month celebrated their successful campaign against Newsom’s trai...

American River, CA – Following the opening of the Nimbus Hatchery fish ladder last week, California Department of Fish a...

Delta Tunnel opponents slam Gov. Newsom's revised budget plan to fast-track project SACRAMENTO - Sacramento — Governor G...

Tom Guzman knows that when Irvine Regional Park drops 800 pounds of fresh trout into the water, you’ve got to show up with a plan. He recently hit the lake and walked away with a beautiful 2.1 pound l...

Dancin Fish Baits has been busy producing spoons, and they're delivering results for Southern California trout anglers t...

Fish Thug Baits has been producing mini jigs that are working well for Southern California trout anglers this season. Wi...

MADE Baits are getting attention everywhere this season. Originally crafted for trout, these baits have proven so effect...